The Three Regimes of System Failure

Most public failures get framed as scandal, incompetence, or corruption. Often true, but analytically lazy. I use three stories, disinfectants, potholes, and Flint water, to show how verification fails in distinct regimes, and why fixes miss when they target the wrong one.

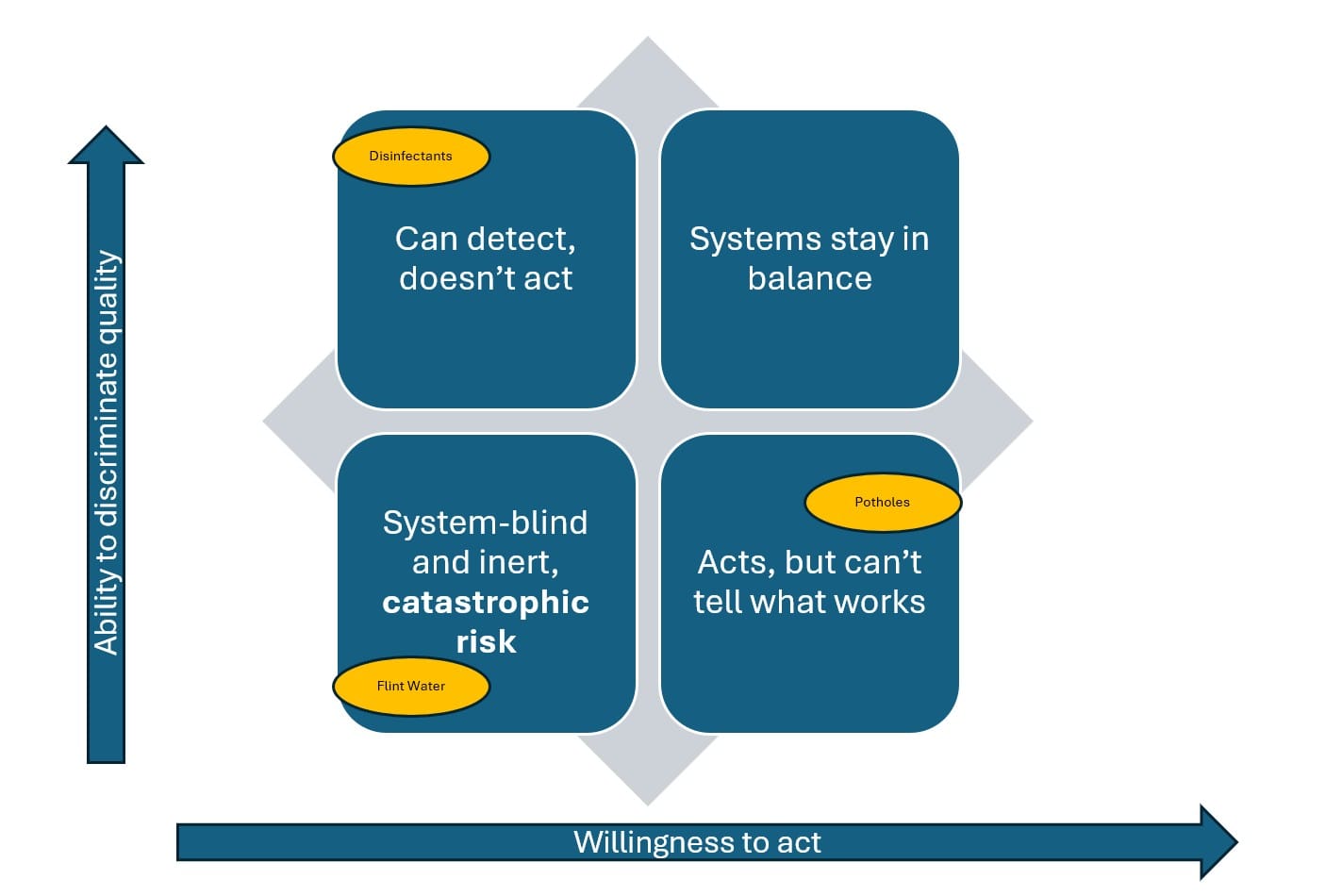

A Map of Verification Failure

The three stories below represent system failures, collapse: disinfectants, Flint water, and potholes are unusually clean as a set because they are orthogonal. Each fails for a different structural reason, yet all converge on the same lived experience: harm that feels obvious in hindsight, and inexplicable in real time.

What unifies them is the death of verification in a living system.

Verification is usually imagined as a procedure, an inspection, a lab test, or a simple checklist. In practice it’s a tightly coupled system.

Colectiv

On a recent trip, I watched a documentary, Colectiv, about a Romanian hospital system with unexplained infections and deaths. It’s good reporting, a solid movie, and I encourage you to watch it.

<Spoiler alert >

The horror wasn’t exotic, just due to ordinary optimization. Investigative reporting uncovered that hospital disinfectants, used across hundreds of hospitals, were heavily diluted at the manufacturer level while being sold and documented as compliant. Then the hospital diluted, as well. All thought they were leaving just enough strength to still fight infection. They weren’t. What was left was watered down so much as to be basically useless.

People paid with their lives. It is also worth noting that this went undetected as a failure mode for years. Years. The paperwork said “sterile.” Bacteria behaved as if disinfecting had not happened.

This is what it looks like when a safety system exists in documents and signage, and fails in the only place it matters, under load. People logged receipt of supplies. They logged usage, faithfully wiping and mopping operating rooms. Yet infections, lost limbs and deaths persisted, because the thing labeled “disinfectant” had become theater.

Here, the system isn’t merely underfunded or confused. It’s performing legitimacy while tolerating incentives such as profit and skimming that overpower checks. Three mechanisms show up cleanly:

- Signature: inspections occur, but they certify appearances.

- Tell: a mismatch between what people privately know and what the system publicly attests.

- Repair path: enforcement credibility, supply-chain integrity (inputs that are hard to counterfeit cheaply), and anti-corruption mechanics that survive local pressure.

This is a safety system that “exists” in documents and signage, and fails in the only place it matters: under load. People logged receipt of the disinfectant supplies. They logged their usage, faithfully mopping and wiping operating rooms. However the deaths, lost limbs, and infections persisted.

A disinfectant supply chain is, in principle, one of the easier safety systems to verify, because the invariant is measurable. A competent system would treat concentration and efficacy as non-negotiable properties, not paperwork attributes. That means independent batch testing on receipt, random audits that cannot be predicted or gamed, and procurement rules that treat chain-of-custody as part of the product, not an administrative afterthought. It also means naming a stop trigger in advance: if product fails spec, it is pulled immediately across the system.

The verification also has to survive incentive pressure. A serious design makes falsification expensive and detection cheap: separate the parties who profit from dilution from the parties who certify compliance, rotate testing responsibility, protect whistleblowers, and ensure that an adverse result forces action rather than negotiation. In other words, the system’s “reality channel” must be insulated from the same forces that create the temptation to counterfeit.

Flint Water Crisis

I have a high school friend who owns a home in Flint, Michigan, so I had a front-row seat to the Flint water crisis. The decision to switch water sources to cut costs was made through a state emergency management structure, meaning the people making the call were structurally insulated from drinking the water. They wouldn't be drinking it. No skin in the game is always a risk signal.

The fallout took the shape it always takes when a governance move is given a technical surface. Water chemistry changed, because the new routing via Flint River had a legacy of industrial pollution. Corrosion control failed. Lead entered drinking water, and the public’s lived experience diverged from the system’s procedural story. People reported that they suffered from lesions from showering in it and were afraid of lead poisoning from drinking Flint’s water. An outbreak of Legionnaires' disease began.

There was a burst of attention. Bottled water (for a while). National outrage. Then the media moved on, and many people assumed the problem had been solved because they stopped hearing about it. But Flint is a decade-scale – yes, ten whole years!– remediation story. As of the City’s current reporting, over 97% of lead service line replacements have been completed, with remaining work tied to permission access, ongoing inventory requirements, and the long tail that follows any distributed infrastructure repair. “Almost fixed” is still not “done,” in the only sense that matters to residents.

In this case, I classify it as a governance failure with a technical mask.

A finance and authority stack makes a series of “legal” moves that are structurally illegible to the public, then offloads harm onto bodies. The technical artifact (water chemistry, corrosion control, lead leaching) becomes the mask for a political-administrative decision system that optimized for budget and plausible deniability.

- Signature: harm is real, but causality is “paper mediated.”

- Tell: lots of memos, jurisdictional seams, and process language.

- Repair path: accountability and authority redesign, plus technical remediation.

A water-source switch is a chemistry-coupled infrastructure change, the kind that should trigger a “prove it before you move” posture. Before any cutover, a competent system would treat corrosion control and lead exposure as explicit invariants, not details: define what must be true before switching, measure it, and publish the stop triggers in advance. Then stage the change with hold points, acceptance thresholds, and authority to halt. Not “we’ll monitor.” More like: if indicators cross X, we revert within Y days, with budget and decision rights already assigned.

After the switch, the verification burden only increases. A serious plan would have used at least one independent sensing channel, not as optics, as redundancy, and a cadence that forced early signal into decision-making before downscale burdens harden.

Flint reads like the inverse. The sensing pathway became contested and delayed, and reversal became politically expensive. That combination is how a technical surface turns into a decade-scale tail.

Potholes

Years ago, in London, a filmmaker asked me a question with a grin that was really a diagnostic probe.

“Michigan roads are infamous,” he said. “Even here in London people joke about the irony. Why would the automotive capital of the world have such bad roads?”

He wasn’t asking about asphalt. He was asking about systems.

Most people reach first for weather. Freeze–thaw cycles. Salt. Heavy trucks. All true inputs. None sufficient as an explanation, because weather doesn’t create persistent failure by itself. Weather exposes whatever shortcuts a system has already normalized.

What changed wasn’t the physics of roads. It was the system’s ability to tell a durable road from a shortcut road, and to force that distinction to matter.

Over decades, road design, inspection, and construction oversight moved from public engineers into private firms bidding on fixed-price work. Engineers, the ones who knew how to evaluate substrate depth, compaction, drainage design, asphalt composition, and lifecycle durability, followed the incentives. They left the public sector for the higher-paying private roles that lived on the other side of the contract. The public sector kept the responsibility. It lost the expertise.

When the discriminative capacity migrated out, the procurement relationship inverted. Instead of vendors being constrained by oversight, the principal became dependent on vendor claims. Oversight remained in name, but thinned into procedure. Checklists. Pay items. Sign-offs. The appearance of control, without the depth to audit the work.

And once the accountability layer weakens, substitution begins. Thinner asphalt courses. Cheaper aggregate. Reduced base preparation. Value-engineered drainage. Each change defensible in isolation. Together, they change the failure curve. A thin layer cracks faster. A poorly compacted base deforms under load. Inferior aggregate absorbs water and fractures. Edges crumble. Drainage accelerates every weakness. The road “mysteriously” deteriorates, and the system responds with more patching, more procurement, more motion.

This is why potholes sit in the quadrant “Acts, but can’t tell what works.” There is spending. There is effort. There are crews. There are projects. But without internal depth, the system can’t reliably distinguish a fix that restores lifecycle integrity from a fix that merely suppresses complaints until the next season. Variance rises. Recurrence becomes normal. The public learns helplessness. The state learns ritual.

- Signature: high activity, low traction, recurring failure under the same operating conditions.

- Tell: oversight becomes procedural while quality becomes opaque, and durability collapses one “reasonable” substitution at a time.

- Repair path: rebuild quality discrimination, in-house competence, and feedback loops before scaling spend, otherwise the system purchases motion, not improvement.

A road system isn’t hard to verify in the abstract. What’s hard is verifying durability when the principals no longer have the competence to judge it.

A competent system would treat lifecycle performance as the invariant, not just conformance on one-time pay items. That means instrumenting the work in ways that can’t be satisfied by cosmetic compliance: independent inspection capacity with the authority to reject work, materials verification, compaction and substrate validation, and acceptance criteria tied to durability, not just completion. It also means writing hold points into the build process, the same way you would in any high-risk cutover: stop triggers, rework requirements, and the ability to pause payment until the invariant is met.

After construction, the feedback loop is part of verification. A serious design treats early failure as a signal to audit upstream decisions, not as weather or bad luck. It builds a protected pathway for recurrence data to force changes in specs, vendor qualification, and oversight practice. Without that loop, you get activity without learning. With it, the system can distinguish “we filled holes” from “we restored integrity,” and balance becomes possible again.

Three Systems, Compared

The map above is about where a system’s protective function collapses. The top-left quadrant describes systems that can detect problems and still fail to act. The bottom-right describes systems that act, spend, and work hard, but can’t reliably tell what works.

The bottom-left describes a darker combination: systems that are functionally blind and inert, and therefore carry catastrophic tail risk. The top-right is the quiet control case, what it looks like when verification still has teeth.

The three dots matter because they keep this from being a thought experiment. They are demonstrated real-life failure modes. They happened to real people, and lives were lost in some cases.

Disinfectants, the Romanian hospital scandal documented in Colectiv, is a case of selective or optional verification. The system could have detected the gap between what was promised and what was delivered. But incentives overpowered checks. Paper stood in for reality, and inspections certified appearances.

Potholes are a case of hollow verification, capability drift. The system acts, budgets, patches, and rebuilds, but has lost the internal discriminative competence required to distinguish a durable fix from a cosmetic one. Without that, the system purchases motion, not improvement.

Flint water is a case of override without a clean return path. Authority makes a move buffered from exposure, then defends it as the consequences surface. The technical layer becomes a mask for a governance decision, and human bodies become the audit log. The tell is time. A decade-scale remediation tail is evidence that the original decision was not governable in reverse.

This is why fixes so often misfire. People prescribe sensors to a system that won’t act. They prescribe enforcement to a system that can’t discriminate. They prescribe “process” to a system that has damaged its return path. The intervention sounds reasonable, and fails anyway, because it’s aimed at the wrong quadrant.

If you want a compact way to use this map beyond these three cases, a simple diagnostic works. Ask two questions.

- Quality discrimination capacity: Can the system reliably distinguish acceptable outcomes from unacceptable ones, durable from cosmetic, sterile from performative? This is the vertical metric.

- Willingness to act: Will the system use what it can discriminate to trigger correction, even when incentives push toward looking away? This is the horizontal axis.

Those two answers tell you where you are. And once you can name the regime, together we can start designing repairs that actually match the failure.

— Madonna Demir, author of Systems & Soul

If you enjoyed this essay, read Capability Drift in Public Infrastructure next, where I go into more detail about potholes and the systems behind them.