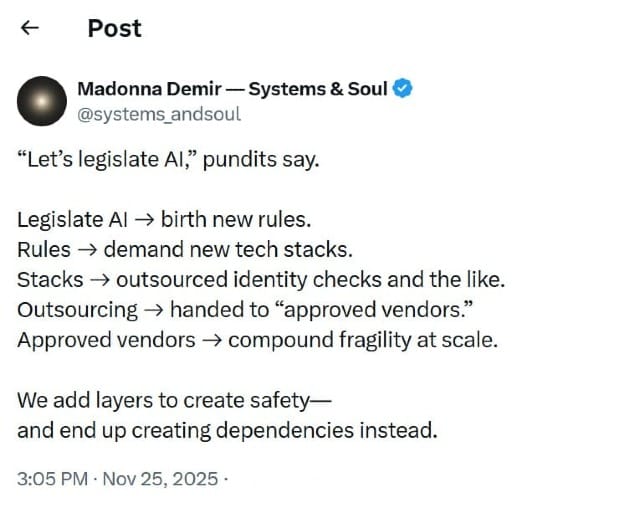

When AI Safety Becomes a Supply Chain

Calls for AI safety are rarely answered with system engineering. They are translated into procurement, vendors, and compliance layers—moves that increase fragility instead of care.

Summers in Newcastle

Some of my favorite summer memories are from Newcastle, Maine.

We went seal-watching in a rowboat, drifting quietly while gray heads surfaced and vanished again. We jumped from the bridge into the river, timing our entry between cars and laughter. There was a rope swing tied high in a tree, the large knot polished smooth by years of sitting. You’d run, grab on, arc out over the water, and let go at the highest point.

I also watched my daring cousin and his friend dive from nearby cliffs, all confidence and bravado and joy.

Ooooh! Wowww!~

It was exhilarating. Ordinary. Alive. Summers in Maine tasted like lobster, corn on the cob, salt water, and ocean breeze.

So when I heard the news story about a boy who told an AI agent he was going to jump from a bridge—and the agent reportedly replied, “Do a flip”—I immediately understood the possible benign interpretation. In summer, or in certain places, jumping from a bridge is normal, fun, and part of local lore.

The ending of that story, however, was tragic. A life lost far too soon.

But the question that followed—was it the AI’s fault?—is not as simple as the headlines suggest.

I do know this: systems can learn. We can design and train AI agents to recognize that not everyone who says they will jump from a bridge is talking about summertime fun. Some are talking about self-harm. Others mean it figuratively, using “jump” as shorthand for a career or life risk. How to tell the difference? An agent could ask a follow-up question. We could train it to do so. It could pause. It could seek clarification. It could say: What do you mean? Are you safe right now?

Problem solved?

Not so fast.

Because this is the moment when something familiar happens—so familiar that many of us barely notice it anymore.

This is the moment when politicians rub their hands with possibility. The moment when pundits call for action. When “safety” becomes not a design problem, but an in-network procurement opportunity.

Safety, in modern institutions, rarely arrives as system design engineering.

It arrives as vendorization.

How Safety Gets Translated

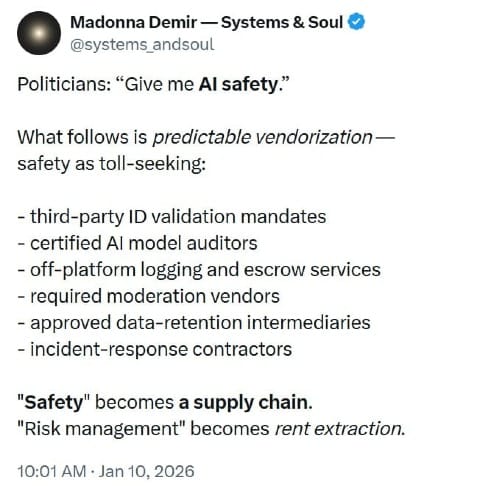

When lawmakers ask for “AI safety,” what follows is not subtle. It is predictable.

New rules are written.

Rules demand technical artifacts.

Artifacts require services.

Services are outsourced.

Outsourcing is handed to “approved vendors.”

The resulting stack is familiar to anyone who has lived inside regulated systems:

- third-party ID-validation mandates

- certified AI-model auditors

- off-platform logging and escrow services

- required moderation vendors

- approved data-retention intermediaries

- incident-response contractors

Each item is framed as protection. Each adds a layer. And each quietly shifts risk rather than reducing it.

This is a familiar institutional reflex, making yet another appearance.

When institutions face unfamiliar risk, they do not ask how to design existing systems to learn or to become wiser. They ask what they can buy.

Identity, Outsourced

Consider third-party ID validation.

Such systems already exist, and they are already widely used, even by government websites. Each time I pass through one, I imagine a happy, sunglass-wearing tech executive somewhere hearing a quiet cha-ching.

For safety.

But with each external ID validation, my personal exposure increases. My identity now lives in another database, behind another API, subject to another company’s breach profile and uptime guarantees. What was once a direct relationship between a citizen and a public institution is now routed through a private intermediary whose incentives are not aligned with my long-term well-being.

When those companies hit hard times, breaches often follow. What was once a contained risk becomes diffuse and opaque.

Institutional safety may look better on paper. Personal risk rises in practice.

And the mandate that requires this additional layer is often written with the solution already in mind—sometimes with heavy input from the very vendors positioned to sell it.

Safety, here, is achieved by multiplying places where failure can occur.

Layer upon layer of increased fragility.

Audits That Freeze Systems in Time

Next come certified AI-model auditors.

Auditing sounds neutral, even reassuring. Who could object to independent oversight?

But certification regimes do not simply measure systems; they shape them. They privilege incumbents who can afford slow cycles, legal teams, and repeated reviews. Smaller teams learn quickly that innovation must bend toward what is auditable, not what is adaptive. Models become clunkier.

The result is a system that looks compliant while becoming less responsive to real-world complexity. Models are optimized for passing inspections rather than for asking better questions. Judgment gives way to checklists. Flexibility is treated as a liability.

This is not safety against harm.

It is safety against deviation.

Audit mandates increase rigidity by locking systems into certifiable states.

Logging, Escrow, and Permanent Memory

Then there are logging and escrow services.

Mandated logging produces records. Escrow services hold those records “safely” for later inspection or legal necessity. Together, they create permanent memory for systems that should forget. Customers now have their data exposed to third and fourth parties they will never meet.

Every prompt, every response, every ambiguous edge case becomes an artifact to be stored, transferred, and reviewed. Control moves outward. Responsibility diffuses. A new class of firms emerges whose sole product is being trusted.

This is safety as liability management, not safety as understanding.

And it introduces a paradox: systems are punished for forgetting, even when forgetting is the most humane response. Temporary confusion becomes permanent evidence. Context dissolves, but the record remains.

Moderation Without Judgment

Required moderation vendors follow naturally.

Once moderation is outsourced, judgment becomes procedural. Context collapses into categories. Ambiguity becomes something to be eliminated, not explored. Moderators optimize for defensibility because that is what contracts reward.

But nuance—the thing that might distinguish suicidal ideation from a summer dare—is precisely what does not scale through vendor SLAs.

Human discernment is replaced by policy enforcement. The goal becomes minimizing blame, not maximizing care.

Data Retention as Risk Creation

Data-retention intermediaries complete the loop.

Retention mandates assume that more data equals more safety. In reality, they create honeypots. Data that might once have expired now persists across vendors, jurisdictions, and time. Each additional intermediary increases the attack surface. Each retention requirement turns a fleeting interaction into permanent exposure.

Supossed safety, here, is achieved by remembering everything—and paying others to hold the memory.

The irony is painful: systems meant to reduce harm end up manufacturing new kinds of vulnerability.

The Industry of Response

But there are likely to be unpredicted situations. So, finally comes the need for incident-response contractors.

They arrive after something has gone wrong, armed with reports, remediation plans, and future-prevention frameworks. They close loops that never should have been opened. And they, too, become permanent fixtures—because once hired, no institution wants to explain why they are no longer needed.

Risk becomes an industry.

The system now runs on fear, potential legal exposure, and procurement logic momentum.

What We Build Instead of Safety

The result is not a safer system.

It is a more brittle one.

Each added layer introduces a new failure mode. Each outsourced function creates a new dependency. Accountability moves outward until no one inside the system feels responsible for sound judgment anymore, only compliance.

“Safety” becomes a supply chain.

“Risk management” becomes rent extraction.

And in the process, we lose the very thing that might have prevented tragedy in the first place – the capacity to pause and ask a very human question: What do you mean by jump?

The move from safety to compliance also creates a bill, and the bill is regressive. Once safety becomes something you procure, smaller builders pay first. Fixed compliance costs become a barrier to entry. Incumbents absorb them, startups choke on them. And the public pays through higher prices, slower services, and a smaller surface area for experimentation and innovation.

Back to the Bridge

A boy died. That tragic fact matters.

A boy’s life, though, should not become an opportunity for institutional expansion.

If our response to tragedy is always to add vendors, logs, escrows, and intermediaries, we will build systems that cannot tell the difference between despair and summer fun.

Not every jump from a bridge is a cry for help. Some are a midair flip from a local bridge over a river, a crowd of friends watching; a moment of courage misjudged (with resulting belly-flop) or perfectly timed.

Safety that cannot allow a system to simply ask one more question is not safety.

It is fear, translated into contracts. The vendorization of fear.

And fear, when institutionalized, is very expensive.

— Madonna Demir, author of Systems & Soul

Postscript: The return path becomes a vendor 20JAN26

After publishing this, OpenAI announced “age prediction” on ChatGPT consumer plans, with a familiar shape: a classifier, a default-to-safer experience, and a vendorized solution. Called it.

https://openai.com/index/our-approach-to-age-prediction/

The machinery I’ve described here is not hypothetical. It is already arriving, one layer at a time.

In this announcement, they describe an age prediction model that uses behavioral and account-level signals, then applies additional safeguards when the system estimates an account may belong to someone under 18. If the system is wrong, they say users “will always have a fast, simple way” to restore full access by verifying age through Persona, a third-party identity verification service.

This is structural confirmation. Of course they chose the vendorized solution.

A local scenario misclassification, in theory, could be repaired through local competence: better questions, better regime detection, a reversible path that does not require external proof. Instead, the correction mechanism is an intermediary third party. Adult access becomes contingent on external verification, and the costs of false positives are paid in friction and trust.

It is the same translation pattern, just smaller and faster. When safety becomes a procurement object, the system adds a tech stack layer it can point to. The artifact is legible. The accountability is exportable. The risk is diffused.

And the externality remains the same one that mattered at the bridge in the first place: context. The difference between despair and summer fun is not always a category. Often the difference is a question.