When Incentives Break the System

A child’s drawing revealed something most systems obscure. Misaligned incentives quietly reshape work, culture, and infrastructure until drift becomes make-work and make-work becomes instability, not from malice, but from obedience to the wrong signals.

Incentive Fragility: How Systems Break When Rewards Drift

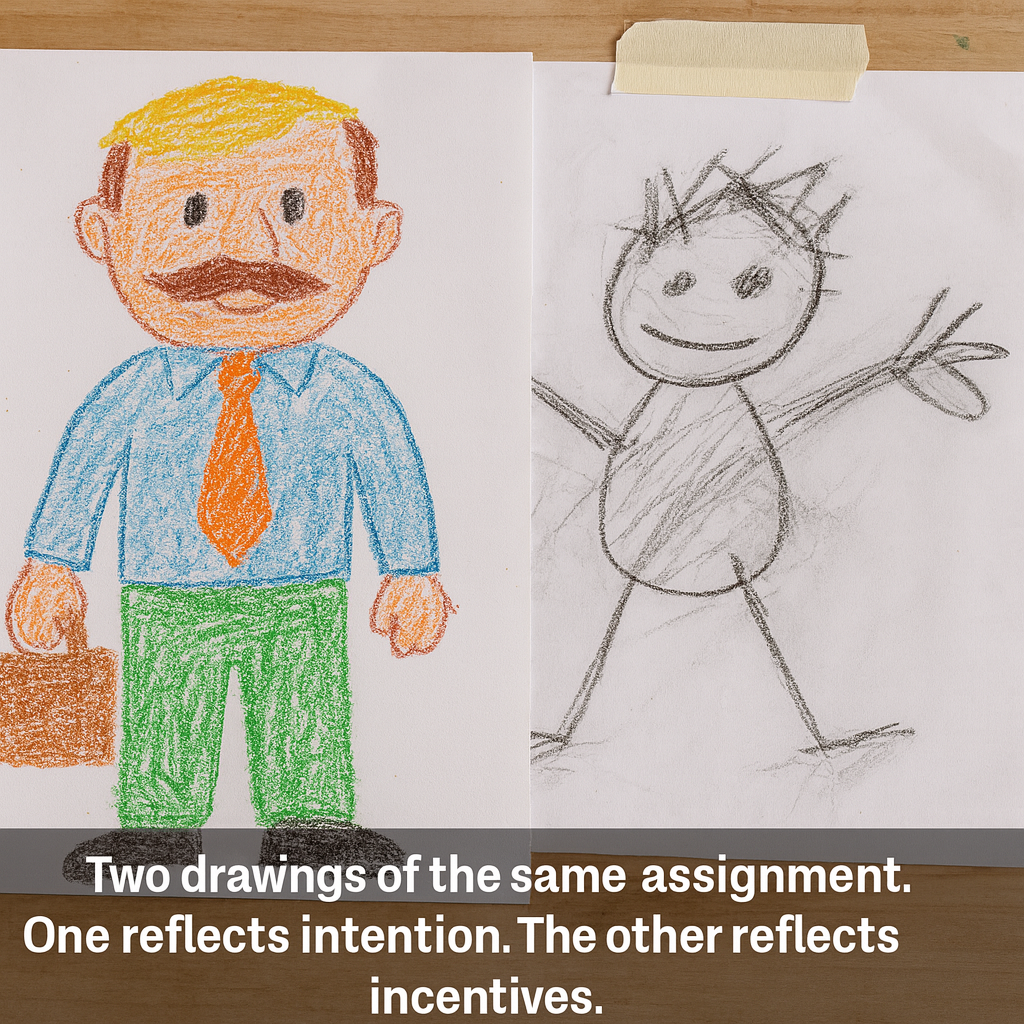

When my youngest son was in kindergarten, his teacher pulled me aside at the mid-year parent-teacher conference with concern.

At the start of the year, the children were asked to draw a man. She pulled out his folder to show me his early drawing. My son had drawn a man with a mustache, a necktie, a shirt, pants, shoes, and a briefcase — all the tiny details a five-year-old boy thinks matter.

Mid-year, she emphasized, here’s what she got when she asked him to draw a person again. Her eyes opened wide as she handed me the next picture.

This time the drawing was sparse.

Rushed.

Missing pieces.

A stick figure with glove-like hands.

“His letter writing is similarly sloppy,” she said, “and this drawing”—she tapped the latest rushed stick figure for emphasis—“shows he isn’t developmentally ready to follow direction reliably. He doesn’t take the schoolwork seriously enough, and his recent rushed work shows this. I'm concerned with his lack of effort lately.”

I asked her, “What happens after they finish their letter practice? Or their drawing of a man?”

She said, “They go to the play area. Toys.”

Of course he was rushing.

The work wasn’t the goal.

The toys were the goal.

He didn’t have a development problem.

He had a correct reading of the system.

The teacher thought she was measuring readiness.

She was measuring speed-to-incentive — and mistaking it for maturity.

His first drawing of a man was fine. It was done without a known system of incentives. Once those were learned, "the faster I draw→ the quicker I can get to the best toys," he mastered them.

This is how systems break.

They think they’re assessing the task.

But they’re really assessing how fast someone can read the reward system.

Whatever you incent, you get.

Systems Are Obedient to Incentives

The kindergarten classroom revealed something most adults forget:

Systems are not moral.

They are structurally obedient to incentives.

They don’t respond to intentions, or instructions, or stated goals.

They respond only to the incentive path embedded in their design.

If the incentive points in one direction and the purpose points in another,

the incentive wins every time.

Systems drift toward:

• the fastest reward

• the lowest-effort route

• the least-risk path

• the behavior that unlocks the next privilege

• the incentive someone accidentally left in the corner of the design

No five-year-old needs a lecture on systems theory to understand this.

A child’s logic is simple:

Do the thing that gets you to the toys first.

Adults call this “cutting corners,” “laziness,” “poor work ethic,” or “not taking tasks seriously.”

But these judgments mistake the symptom for the structure.

Most “undesirable behavior” is not a character flaw.

It is the correct adaptation to the system’s true reward surface.

The teacher believed she was assessing:

• care

• focus

• readiness

• development

But the system she built was assessing something else entirely:

speed-to-incentive.

And she mistook the honest output of her own system design for a deficiency in the child.

This is the quiet tragedy of most systems.

They misread their own signals,

punish the correct adaptations,

and reward the distortions.

A system’s outcomes are never mysterious.

They are simply the incentives made visible.

Whatever you incent, you get.

Drift: When Systems Stop Making Sense

Before a system drifts, it holds steady — like koi in a pond.

Koi don’t need rules or supervision.

They don’t need correction.

They move with calm precision because their environment gives them stable cues:

a warm patch of water,

a predictable current,

a small glimmer of light,

a steady supply of oxygen.

A koi pond stays in balance because its incentives are simple and consistent.

The koi follow the quiet logic of the environment.

Stable incentives → coherent behavior.

Unstable incentives → reactive behavior.

Disturb the pond — cool the water, block the light, churn the current — and the koi will not become “disobedient.”

They will become reactive, erratic, pulled into motions that have nothing to do with their nature and everything to do with the environment confusing them.

Human systems behave the same way.

Wherever incentives diverge from stated purpose, drift appears.

The kindergarten classroom wasn’t an exception.

It was an early demonstration of a universal system failure.

When incentives are steady, people move with clarity.

When incentives are noisy, people drift.

When incentives contradict themselves, people thrash.

And when incentives reward the wrong thing, people move exactly in that direction.

Drift, then, is the predictable consequence of a system that has stopped making sense to the people inside it.

It begins quietly:

• a student rushing through drawings to be first to pick out the best toys

• an employee polishing a slide deck instead of solving the problem

• a manager optimizing for optics rather than clarity

• a department spending more time documenting work than doing it

• a public program performing compliance rituals instead of outcomes

• a team pretending alignment to avoid emotional penalties

• a supply chain rewarding throughput over traceability

No one intends this drift.

Drift is what happens when the environment’s cues become contradictory —

when the pond churns.

Every participant is simply reading the real incentive surface,

not the stated one.

Drift is not misbehavior.

It is adaptation.

By the time the “problem” is visible, the drift is already the culture.

Once culture cements, it becomes structure.

And once structure aligns with distortion, fragility is already forming.

When Neural Systems Learn the Incentive, Not the Story

This dynamic is not unique to human systems.

Neural networks behave the same way.

A model does not learn what its designers intend.

It learns what its reward function makes easiest to optimize.

If the reward surface favors speed, the model learns shortcuts.

If it favors correlation over causation, the model learns mimicry.

If it rewards proxy metrics instead of ground truth, the model learns distortion.

The system is not misaligned because it is careless.

It is aligned perfectly — to the incentives it can see.

When humans are surprised by model behavior, they are often reacting to the same mistake the kindergarten teacher made: mistaking obedience to incentives for failure of understanding.

The model did not drift.

The reward did.

Make-Work and Payroll Theater: When Drift Becomes the System

Drift doesn’t stay small.

Once a system begins rewarding the wrong thing, the distortion compounds until the distortion becomes the work itself.

Entire industries run this way.

On the surface:

• meetings

• reports

• dashboards

• KPIs

• compliance rituals

Underneath is a quiet economy of make-work designed to satisfy incentives no one will say aloud.

Local-content rules force companies to perform labor not because it creates value, but because it unlocks market access. In UBI Dressed Like Work, I described a company that received fully assembled goods from one country, disassembled them into subassemblies in a second, then reassembled those subassemblies with local labor in a third — simply to access a market.

In transportation, subsidy structures keep unprofitable routes open not because they serve customers, but because they serve political stability.

Corporate overstaffing persists not because the tasks require it, but because incentives demand headcount optics, tax advantages, or the preservation of internal fictions.

This is the theater people inhabit every day —

payroll theater,

employment as staged necessity.

We call these “jobs,” but many are closer to income-distribution mechanisms disguised as productivity — a way for systems to maintain equilibrium by giving citizens the illusion of needed roles, while the true incentive is simply: keep everyone attached to the machine.

The individuals inside these arrangements are not deluded.

They know the difference between value and theater.

But their survival depends on reading the signals correctly:

Do what preserves the fiction, not what improves the system.

This is not a personal failing.

It is the rational optimization of a misaligned design.

When drift is rewarded long enough, it becomes institutional memory.

When theater is rewarded long enough, it becomes culture.

And once a culture or organization identifies more strongly with its theater than with its purpose, fragility is already baked in.

Emotional Labor: The Hidden Infrastructure of Every System

There is another layer of incentives most systems never acknowledge —

the emotional labor that keeps everything from collapsing under its own weight.

Every workplace, every family, every institution relies on an invisible infrastructure of people who:

• smooth conflicts

• absorb friction

• translate messy instructions

• carry the hidden cognitive load

• do the relational work that makes the technical work possible

• keep morale from dropping below the line of dysfunction

This labor is rarely named.

Never measured.

Almost never rewarded.

But systems depend on it.

And because it is invisible to metrics, it is invisible to incentives.

Which means the people who perform it are often penalized for the very work that holds the system together.

They are labeled “overly emotional,” “not strategic,” “not promotable,” or “not focused,” because they are doing work the system refuses to see — work with no slot in the KPI menu. Yet the same folks are often also called the glue that holds the team together.

The burden grows until something breaks:

burnout, resignation, disengagement, or a quiet withdrawal of the emotional scaffolding that once kept everything upright.

When emotional labor collapses,

systems fail in ways no dashboard can predict.

You can’t measure the absence of something you never measured in the first place.

You can’t incentivize support when the system pretends support is free.

Just as traceability collapses in technical systems when components disappear into shadow channels — something I explored recently in an SIA —

traceability collapses in human systems when care disappears into silence.

Drift in emotional labor is the earliest sign of cultural fragility,

but the system, blind to this load, often interprets it as a personal failing rather than a structural one.

A system that ignores its hidden infrastructure will inevitably misdiagnose its own instability.

And a system that penalizes the people carrying that infrastructure is already on the path to failure.

Vendorization and Layer Incentives: How Modernization Breeds Fragility

Drift doesn’t only happen inside people.

It happens inside infrastructure.

Every time a system feels pressure to “modernize,” the first instinct is to add a layer:

A new vendor.

A new SaaS subscription.

A new middleware tool.

A new compliance platform.

A new oversight mechanism.

Each layer arrives wrapped in the language of improvement:

efficiency, safety, visibility, modernization.

But each layer also arrives with its own incentives:

• subscription renewals

• maintenance contracts

• integration fees

• update cycles

• “approved vendor” status

• contractual minimums

• system lock-in

By the time all the stakeholders have gotten their beaks wet, the original purpose is buried under a stack of dependencies.

The incentives shift from solving the problem to preserving the layer,

because preserving the layer is where the money flows,

where the access flows,

and where the organizational reward flows.

And once every layer demands its cut,

you don’t have a modernized system.

You have a fragile one.

A system meant to streamline becomes slower.

A system meant to simplify becomes more complex.

A system meant to reduce risk creates new points of failure—SIA

We rarely call this by its real name:

incentivized fragility.

Fragility created not by incompetence,

but by a design in which every actor is optimizing for their own incentive surface.

The kindergarten lesson repeats at scale:

If toys follow fast work, you get fast work.

If revenue follows layers, you get layers.

If incentives follow opacity, you get opacity.

No system anchored in layer incentives can remain stable.

It will drift toward needless complexity, vendor dependence, and the most expensive failure mode of all:

a loss of visibility.

Which brings us to the point where incentives stop merely distorting the system…

and begin blinding it.

Traceability Collapse: When Systems Blind Themselves

In every safety-critical environment — aviation, medicine, semiconductor fabrication, food systems, manufacturing — one capability determines whether small issues stay small:

traceability.

When something breaks, you must be able to trace the fault backward faster than it can propagate forward.

Healthy systems maintain lineage — a chain of custody.

They know where each component originated,

how it was made,

who touched it,

which factory and shift produced it,

where it was tested,

who packed and shipped it,

what drifted along the way,

and what might now be contaminated.

Traceability is the narrow door.

Without it, no system can contain its failures.

But incentives rarely reward traceability.

They reward throughput.

They reward volume.

They reward speed.

They reward vendor substitution.

They reward finishing faster than the next person.

This is the same kindergarten logic, written in adult machinery:

If toys follow letter-writing worksheets, the letters get rushed.

If revenue follows output, the process gets blurred.

In technical systems, this blur becomes catastrophic.

• Parts get relabeled.

• Subcomponents get swapped for cheaper alternatives.

• Compliance becomes checkbox theater.

• Third-party workarounds grow in the shadows.

• Vendor substitutions happen off the books.

• Documentation drifts away from reality.

Systems begin performing the outline of traceability

without retaining the substance. SIA

The result is a system that can no longer see itself.

A defect that should have been isolated at a single line or batch becomes a system-wide threat.

A small deviation becomes a black-box event.

A minor drift becomes a cascading failure.

People didn’t fail.

The incentives did — rewarding speed over visibility, and volume over chain of custody.

Traceability collapse is the purest form of incentivized blindness —

a system losing its ability to understand its own behavior.

When a system can no longer see itself,

it cannot protect itself.

This is the point at which drift turns into fragility,

and fragility turns into collapse.

How Fragility Forms

Fragility isn’t a surprise.

It isn’t a malfunction.

It isn’t the sudden appearance of risk where none existed before.

Fragility is what accumulates when a system obeys its incentives instead of its intentions.

It begins as drift — a child rushing through letters for toys.

Then becomes culture — adults rushing through work for optics.

Then becomes structure — organizations building layers that reward preservation over purpose.

Then becomes blindness — systems losing the ability to trace what they produce, how they produce it, or why failures cascade.

Fragility is simply drift allowed to mature.

Every brittle system carries the same quiet signature:

• misaligned incentives

• invisible labor

• bloated layers

• shadow channels

• vanishing traceability

• unmeasured burdens

• unexamined assumptions

• optics replacing outcomes

Each on its own is survivable.

Together, they form a closed loop — a system that cannot sense its own state and cannot correct its own course.

That is fragility:

a system whose feedback loops are louder than its truth loops.

A system that interprets correct adaptation as deviance.

A system that punishes the people who are reading its architecture accurately.

A system that rewards the illusions that keep it intact.

Fragility is the price of a system design that refuses to confront its incentives.

And by the time fragility becomes visible, the collapse has already begun.

Not the dramatic collapse — the structural one.

The collapse of meaning.

The collapse of traceability.

The collapse of clarity.

The collapse of resilience.

A robust system is one where incentives reinforce the purpose.

A fragile system is one where incentives compete with it.

An antifragile system is one where incentives reveal misalignment early enough to correct it —

and the system becomes better for the correction.

This is the doctrine:

A system’s fate is written in its incentive surface.

If the incentives blind it, the system will drift into fragility.

If the incentives illuminate it, the system will self-correct.

The kindergarten lesson scales:

If toys follow letters, the letters get rushed.

If rewards follow theater, the theater becomes the work.

If incentives reward opacity, the system goes dark.

If traceability disappears, containment dies.

If containment dies, every small error becomes a system-wide risk.

Fragility isn’t mysterious.

It’s predictable.

It’s designed.

It’s earned by incentive drift.

Whatever you incent, you get.

And what you get shapes the entire trajectory of the system —

quietly at first,

then all at once.

Closing

The kindergarten story wasn’t just about a rushed drawing.

It was an early glimpse into how all modern systems lose their way.

They begin with clarity.

They drift toward incentives.

They accumulate theater. Then they reward noise and unintended drift, even unintentionally.

They punish truth.

They add layers to fix the layers.

And eventually, they can no longer see the mechanisms shaping their own behavior.

Fragility is not the moment a system breaks.

It is the long, quiet period in which the system becomes blind to itself —

when readiness is mistaken for immaturity,

when theater is mistaken for value,

when compliance is mistaken for safety,

when throughput is mistaken for traceability.

Most systems aren’t failing.

They’re obeying.

They’re following the incentives we built for them,

whether or not those incentives still reflect design intent or even why the system exists at all.

If we want better outcomes, we don’t need more layers, or rules, or oversight.

We need incentives that reinforce the work rather than distort it.

Incentives that reward clarity over noise.

Traceability over speed.

Care over performance.

Truth over theater.

Systems don’t become resilient by accident.

They become resilient when their incentives illuminate the path back to purpose.

Because in the end, the architecture is simple:

A system will always tell you what it truly values.

All you have to do is look at what it rewards.

— part of the Future of Work Series by Madonna Demir, author of Systems & Soul

Related essays in the Future of Work Series →

On incentives and drift:

• UBI Dressed Like Work

• Am I Stuck in a Bullshit Job?

• The Gen Z Stare

On fragility and visibility:

• Why LED Speed Signs Create New Hazards (SIA)

• Shadow Chains and Traceability Collapse (SIA) — vendor stacks → traceability failure → containment loss

For more on how incentives shape modern work, see this related piece →